Have you heard traffic move during the net and wondered what exactly it is that’s going on? This is the place to learn about radiograms, such as what they include, how they’re read, and how they’re delivered.

What is a radiogram?

A radiogram is essentially a standard format for messages. It allows amateur radio operators to use a consistent layout and format for moving messages, called traffic, around the world.

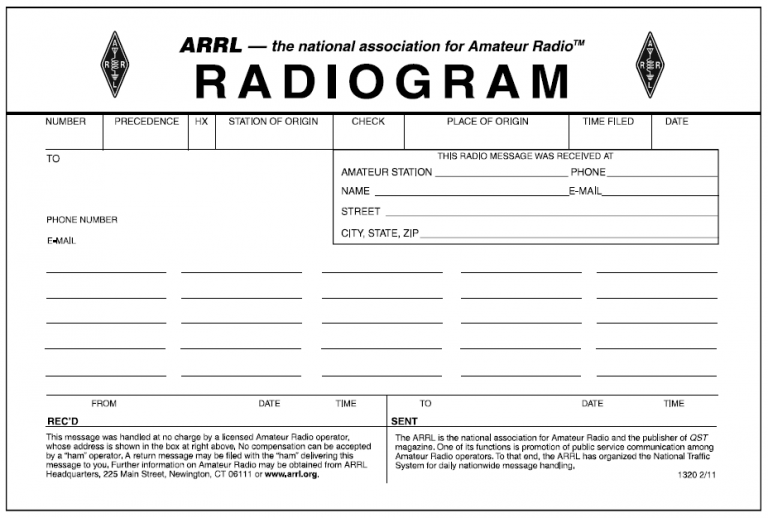

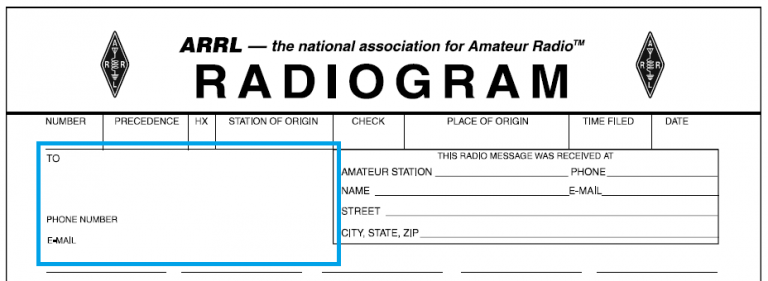

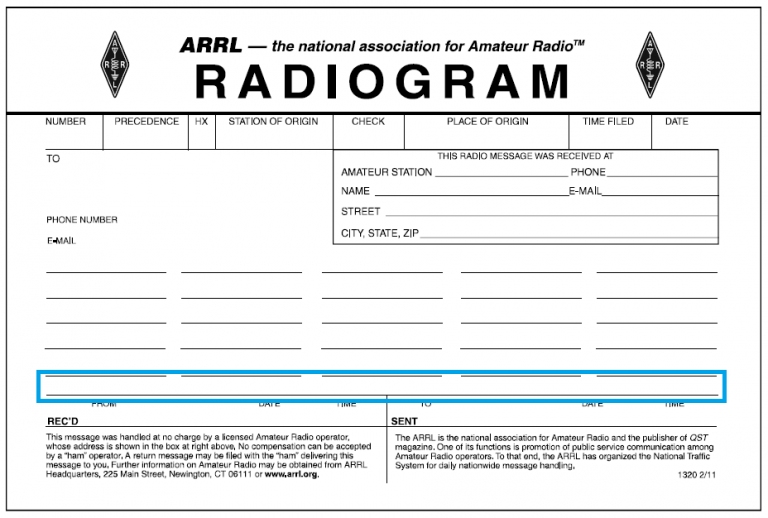

Here is what a radiogram looks like. While they come in various formats (green tear-off pads, PDFs that can be printed on plain paper, spreadsheet files, …) their content remains the same. Don’t worry about what everything is just yet; we’ll start explaining shortly.

Once the message is written, the goal is to have that message arrive at its destination with the exact same content as it started with, word for word and letter for letter.

Parts of a radiogram

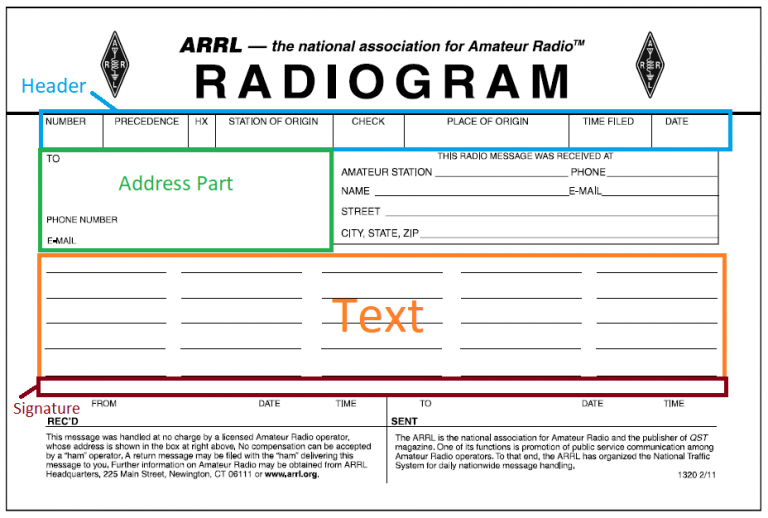

There are some edge cases to what a radiogram might contain (to the point that the template above doesn’t include those parts specifically). We’ll cover the more common edge cases in a deeper drive. For now, let’s focus on the base elements of a radiogram:

- Header

- Address Part (the destination)

- Text (the message)

- Signature

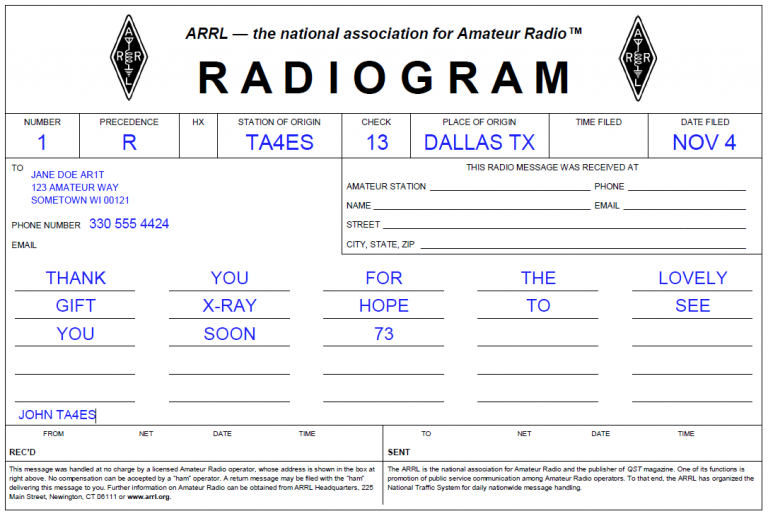

Your first radiogram

Let’s try out putting together your first radiogram. The current date is November 4 based on Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), your name is John Taxpayer, amateur callsign TA4ES, and you are in Dallas, Texas. You want to send a message to a friend of yours, Jane Doe, at 123 Amateur Way in Sometown, Wisconsin, 00121, and her phone number is 330-555-4424. Her amateur callsign is AR1T. In your message you want to say, “Thank you for the lovely gift. Hope to see you soon. 73.”

You may want to grab a blank radiogram and fill it out as we go, and then compare what you have with the example that follows below.

Click here to download and print a PDF version of the radiogram.

Click here to download a fillable PDF version of the radiogram.

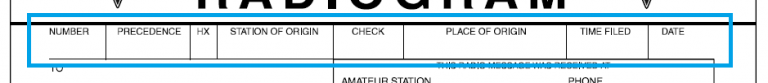

Header

We begin by completing the header.

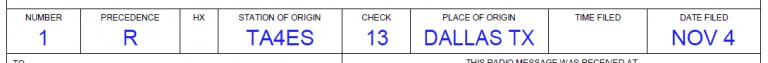

Number: This is a sequential number that you assign to your messages as you write them. Your first message is 1, your second message is 2, and so on. Given this is your first message, the message number is 1.

Precedence: Messages that aren’t emergency, welfare, or otherwise a priority item are characterized as Routine. Put R in the precedence box.

HX: This would be a special instruction called a handling instruction. It isn’t a required item, and we do not have any handling instructions, so we’ll leave this blank. But, here’s a list of valid handling instructions and what they mean.

-

-

- HXA (followed by number): Collect landline delivery authorized by addressee within X miles. (If no number, authorization is unlimited)

- With today’s free long distance plans, you should rarely, if never, encounter this handling instruction.

- HXB (followed by number): Cancel the message if it’s not delivered within X hours of the filing time (this will be filled in on the header block). Once cancelled, send a service message back to the originating station to let them know.

- This is used in cases where the message becomes pointless after a certain amount of time. These types of messages should be sent at least as a Priority message.

- HXC: Report the date and time of delivery back to the originating station.

- This lets the originating station know that the message was delivered, as well as what date and time.

- HXD: Report to the originating station the identity of the station you received the message from, as well as the date and time you received it. Also, report the identity of the station to which you relayed the message along with the date and time, or if you delivered it to its destination, report the date, time, and method of delivery.

- This is used to track a message as it moves through the NTS. It is quite painful, and should only be used if absolutely necessary.

- HXE: The delivering station should ask for a reply from the addressee, and then originate a message back with the reply.

- Some stations would like to receive a reply, and can either indicate it in the message text or here in the handling instructions.

- HXF (followed by number): Hold delivery until (specific date).

- Commonly seen in birthday greetings, this ensures a message is not delivered too early.

- HXG: Delivery by mail or landline toll call not required. If toll or other expense involved, cancel message and service originating station.

- While the goal of any radiogram is to deliver it to its addressee, this instruction indicates that if the delivering station has to incur an expense to complete the delivery, to instead cancel delivering the message and to let the originating station know.

- HXA (followed by number): Collect landline delivery authorized by addressee within X miles. (If no number, authorization is unlimited)

-

Station of origin: You are the origin of the message (the originating station), so your callsign goes here – TA4ES from our example above.

Check: This is a count of the words in your message, and you would normally fill this in after you finish the text section and count how many words are there.

For our message, which is, “Thank you for the lovely gift. Hope to see you soon. 73” it turns into 13 words in the text part of the message, and we’ll explain in greater detail how we came to this number in a little bit. For now, write 13 in the check.

Place of origin: Since John lives in Dallas, Texas, you place DALLAS TX without any punctuation, and you use the two-letter state abbreviation.

Time filed: It’s only important to note the time if the message has some time constraint on it, which is covered in the deeper dive. It’s typically blank on most messages, and given there are no time constraints on this message, leave this blank.

Date: Using the first three letters of the month’s name, we put NOV 4 in the date box. This is the date you introduce the message into the traffic system, such is by checking in to the DFW traffic net and saying you have one message going to Wisconsin. It’s not the date you write it; it’s the date you first try sending the message along through the traffic system.

It’s important to note the date and time are based on UTC rather than your local time zone. This is to help standardize this information so we do not need to track time zone information, or worse, try to translate it on the fly, as the message is moving through the traffic system.

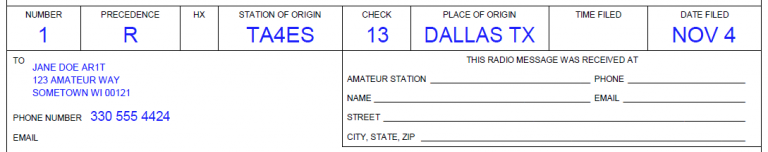

At this point, the header on your radiogram should appear like this:

Address Part

This is where the message is going.

While many radiograms are sent to other amateur radio operators, the recipient of the message does not need to be an amateur radio operator.

The basic format for the address part is:

FIRST LAST CALLSIGN

ADDRESS

CITY STATE ZIP

PHONE NUMBER ### ### ####

Notice that there’s no punctuation in the city, state, and zip line, nor in the phone number. Also, if the recipient isn’t an amateur radio operator, we simply do not include a callsign.

Using this format, we can complete the address part to read:

JANE DOE AR1T

123 AMATEUR WAY

SOMETOWN WI 00121

PHONE NUMBER 330 555 4424

Here’s what the radiogram should look like thus far. It’s OK that email is blank as we do not have an email address, but the phone number is important as it is what will very likely be used to deliver the message.

Text

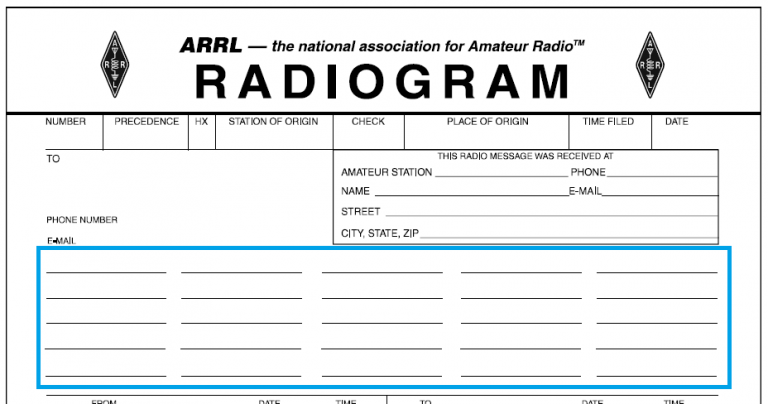

Now we can write the message. Notice how there are 25 blank lines in the message area:

This is where we write the message, one word per blank line. For reference, the message text is:

“Thank you for the lovely gift. Hope to see you soon. 73.”

In a radiogram, periods are written as either the letter X (“initial x-ray”), or the word X-RAY. Either way, this indicates an end of a sentence. To help clarify, if your message was, “How are you?” the question mark would be written as QUERY to indicate a question.

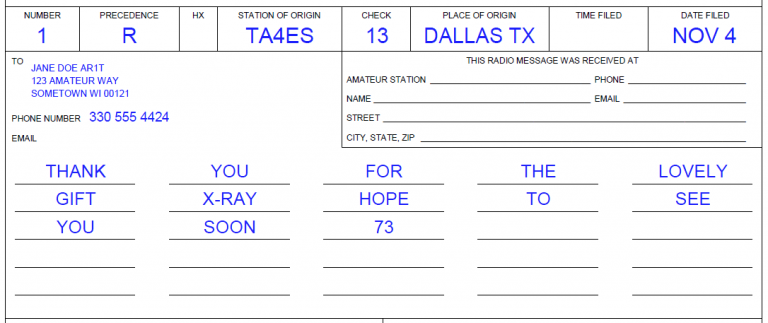

Using this method, we will write the text of the message like this:

THANK YOU FOR THE LOVELY

GIFT X-RAY HOPE TO SEE

YOU SOON 73

Notice how we did not place X-RAY between SOON and 73? When wishing someone 73 at the end of a message, we generally do not include an X-RAY as it’s automatically implied. The only exception would be to include it for clarity. For example, if the end of your message was “ON AUGUST 10 73” it could be confusing this way, so we would instead say “ON AUGUST 10 X-RAY 73” to help better separate the date from wishing someone 73.

Items like X-RAY and QUERY count as a word when filling in the check, so counting what we have above, there are 13 words, and this is why we write 13 in the check.

We almost have a complete radiogram to send:

Signature

Right underneath the message text, almost in a squished fashion, is where the signature goes.

This is quite easy: you sign it with your first name and your callsign.

JOHN TA4ES

Our radiogram is finished and ready to send over the traffic net.

Sending your radiogram on the traffic net

Your first radiogram is ready, but how do you submit it to the traffic net so it can make its way to Wisconsin?

Click here to learn how to send your radiogram >>>